|

|||||

|

|

GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN ARTIST, ROBOTICS

by PAUL BARBERAPublished: January 2020

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman Artist, Robotics

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman is a cybernetics artist specialising in large-scale public installations based in Perth, Western Australia. It was fascinating to go behind the scenes to see Geoffrey’s studio that not only served as a workspace but also as a repository for his impressive collection of vintage electronics. His knowledge and passion for automata/science fiction/computer science makes his approach to his work unique and makes for a different studio space to those that I usually see....

|

|

EXTERNAL CYBERNETICS

by SABEERAHPublished: 7 February 2019

External Cybernetics

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, is an artist like no other. Geoffrey has a background in Computer Science and has exhibited in Perth, Sydney, Melbourne, Singapore, Denmark, New York, and London. He creates installations utilizing technology and software but what sets him apart is that in order for his installations to work they require human interaction. This required human component classifies his art as cybernetic art. All of his pieces utilize sensors that detect people as they come closer to the artwork, software, and other mechanics to create installations that either move, light up, open, close, etc. The purpose of his work is to explore the relationship we have with technology and to form a creative and playful connection to his art and human interaction. Much of his inspiration comes from "robotic" tales of "man-made beings" such as Frankenstein, Pinnochio, etc. [1] He utilizes technology to parallel these stories and by turning them into reality. Geoffrey states, "When I complete an artwork, I like to watch it respond to the audience. I watch to see how the play between the artwork and the audience." According to British cybernetic artist and theorist Roy Ascott, this is an example of behavioral triggers. Ascott defines behavioral triggers as, "Where the artist is interested less in his own behavior than in the behavior of the spectator." This behavior seems to be much of the driving force and sole purpose of his work. This the reason why all of his works calls for such interaction. He also includes mirrors in many of his works to highlight behavioral triggers and relationship between the art and the observer and vice versa. Much like the work of Parisian art research group, Groupe de recherche d'art visual or GRAV for short in the early 1960s whom Geoffrey seems to be heavily influenced by share the same sentiment towards their work. [2]An Art Exhibit That Is Truly Moving, At The

Morris Museum

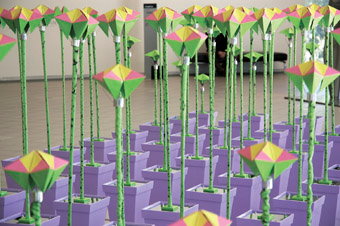

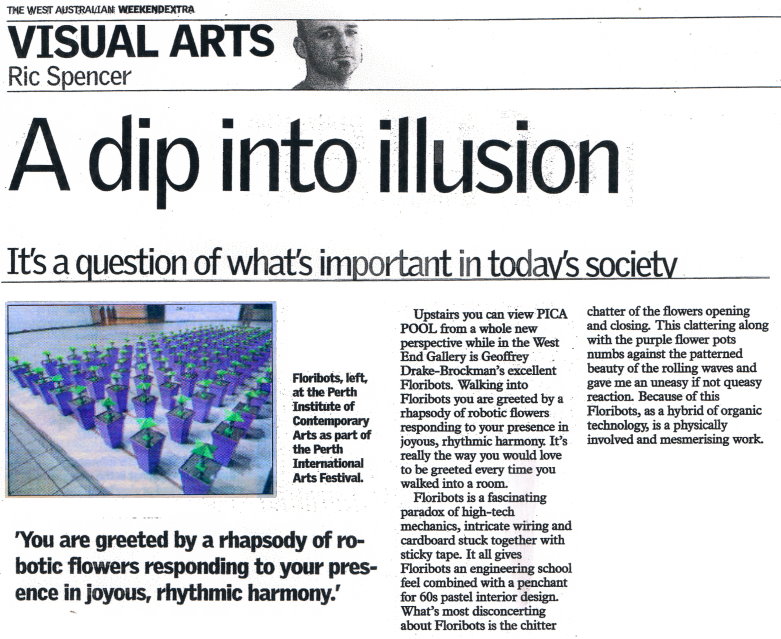

...The other show-stopper is Floribots.

It’s a “garden” with 128 origami-style flowers that sprout, undulate, shimmy and dance in seemingly random patterns, triggered by audience motions captured by sensors.

“They all talk to each other,” Australian artist Geoffrey Drake-Brockman said of the faux-plants, operated with computer power equivalent to a couple of digital televisions.

Installation was challenging; a pair of nor’easters knocked out power at the Morris Museum for the better part of a week preceding the opening.

“Fortunately, the room has good natural light,” said Drake-Brockman, whose inspiration came from children’s paper toys variously known as “fortune tellers,” “cootie catchers” or “chatterboxes.”

He holds degrees in computer science and visual art. Automated projects like Floribots ideally marry the two, he figured. The flower-bots can grow bored by repetitive crowd motion. No motion, and they may clamor for attention. Over-stimulation can make them chaotic. It’s an uncanny commentary on how we interact with technology.

“This sees you and reacts to you, as a technological ‘other,'” Drake-Brockman said. “It’s a process that’s under way in society. We all carry phones and talk to them.”

One can imagine Stephen King’s version of Floribots. Fortunately, there was no need to run for our lives. Not on this visit, anyway.

“It’s quite happy now!” observed Drake-Brockman.

...

Photo: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman and companions travelled from Australia to display his ‘Floribots’ kinetic artwork at ‘Curious Characters’ exhibition at the Morris Museum, March 15, 2018. Photo by Kevin Coughlin

THE POWER OF SIMULATION: SEEING OUR HUMANITY IN A TECHNOLOGICAL WORLD

by MEGAN REEDPublished: Fall 2018

The power of simulation: seeing our humanity in a technological world

Gong for “Hairbrush”

by WILLIAM YEOMAN

Published: 26 June 2018

Gong for “Hairbrush”

Perth artist

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s interactive light sculpture

Surface for the new Perth Children’s Hospital has been

shortlisted for US-based CODAWorkx organisation’s World’s

Best Commissioned Art and Design Project.

Perth artist

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s interactive light sculpture

Surface for the new Perth Children’s Hospital has been

shortlisted for US-based CODAWorkx organisation’s World’s

Best Commissioned Art and Design Project.Drake-Brockman’s artwork, which hospital staff have nicknamed The Hairbrush, is visible from the central atrium of the hospital, where its multi-coloured illumination patterns create the impression of an upside-down pond or billabong.

When people walk underneath the work, sensors pick up their presence and a virtual stone is thrown into the artwork’s virtual pond, causing light ripples to travel out over the virtual water surface. Multiple ripples can disturb the surface at the same time- resulting in a complex interplay of interference patterns.

Drake-Brockman says Surface is the largest interactive 3D LED matrix in the world, with over 16,000 pixels and10m by 5m in overall size.

“The idea is that Surface forms part of the ‘healing environment’ of the hospital — it’s meant to be part of an overall experience that’s as positive as possible for sick kids,” he says.

There is also a hidden feature.

“Occasionally its software mind gets excited by lots of people interacting with it,” Drake-Brockman says. “Instead of a stone being thrown into the pond, a beach-ball is rolled in.”

The CODAWorkx World’s Best Commissioned Art and Design Project is a popular vote award. To vote, visit codaworx.com/awards/codaawards/2018/top100.

The Creator vs. The Created: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

by LAURA SHIRKPublished: 25 April 2018

The Creator vs. The Created: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

Before finally

combining his top two interests: art and programming,

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman consciously separated one from the

other. As different as black and white, he believed that

they represented something opposite in life: aesthetics and

shared experience vs. technical and singular. Over time,

themes such as computation and simulation started to appear

in his work and he broadened his way of thinking. The artist

asked the question: what is it that makes an individual?

With a background in computer science, he went on to become

a cybernetics artist specializing in large-scale public

installations. Bringing together art and technology, he

creates work that initiates dialogue between viewer and

object and interacts with the audience. By representing

human emotions in a technological context, the Australian

aims to connect with people across the globe.

Before finally

combining his top two interests: art and programming,

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman consciously separated one from the

other. As different as black and white, he believed that

they represented something opposite in life: aesthetics and

shared experience vs. technical and singular. Over time,

themes such as computation and simulation started to appear

in his work and he broadened his way of thinking. The artist

asked the question: what is it that makes an individual?

With a background in computer science, he went on to become

a cybernetics artist specializing in large-scale public

installations. Bringing together art and technology, he

creates work that initiates dialogue between viewer and

object and interacts with the audience. By representing

human emotions in a technological context, the Australian

aims to connect with people across the globe.Encouraged to interpret his body of work as a sequence (and not a series), Drake-Brockman’s creative process is based on concept. Connected by lasting threads and a trail of unanswered questions (to be picked up at a later date), his sequence is free of boundaries. Moving between the abstract and the figurative, the creative process remains the same. Following the concept: the step-by-step process of learning how to technically execute that concept. Coupled with conceptual thinking, he has a technical approach to color and color combination and orbits and trajectories. A reflective surface (more specifically, a mirror) is repeated as a motif throughout his work. He comments that in addition to enhancing the aesthetic of the installation, a mirror is used to show the reflection of the viewer back to its owner and trigger interactivity – even before switching on the technology.

As a third layer, the element of reflection leads to the artist’s fascination with robot mythologies: popular stories about “made-beings” (think Pinocchio or Frankenstein). “This inclusion is deliberate, as I see every created being as a kind of mirror. The implication is that the relationship between creator and created is ultimately reciprocal,” shares Drake-Brockman. A way to capture the attention of his audience and investigate the current cultural scene, the familiar story remains relevant to the digital age.

With an imaginative, innovative and a wide-ranging portfolio, it isn’t hard to believe that the artist has a “backlog of ideas” on hand to express himself. While he creates the conditions for interaction, he doesn’t believe that he has full control of audience engagement. He likes to stand back, watch, map patterns and think about the back and forth that organically unfolds between artwork and audience. Depending on the location of the exhibition, he is able to generate an increased level of engagement. For example, in comparison to a gallery space, a public space allows for maximum opportunity for engagement. Whether placed by the train station or on the beach, his life-sized installations draw attention from passers-by and enforce no traditional rules.

As part of its Curious Characters exhibition, Drake-Brockman is currently exhibiting three main interactive artworks at the Morris Museum (Morristown, NJ). On display: Floribots, Coppelia One and Parallax Dancer. As noted online: the three artworks embody quite different interactive modalities – a collective organism, a humanoid robot and an augmented reality installation, respectively. Linking the trio and fitting the automata theme of Curious Characters, each one responds to the audience and shares in the exchanges of the reciprocal relationship.

A plant-based, mechanical garden network, Floribotsis made up of 128 origami blooms with “hive mind” characteristics. It has already been awarded ‘best in show’ for Curious Creatures. First exhibited in 2005, Floribots revealed emergent behavior: a type of behavior that is not anticipated. While the installation expresses a number of overall states: bored (under-stimulated), in-between, erratic (over-excited) and asleep, each individual flower within the set experiences its own emotional states. “The more adept we become as creators, the more complex our creations – leading to greater emergent behavior with less predictability,” adds Drake-Brockman.

Described as “same expression, different domain,” Coppelia One and Parallax are both based on the same real-life prima ballerina (Jayne Smeulders, West Australian Ballet) and serve as a figurative representation of humanity. Positioned side-by-side in the exhibition, the “set of twins” face, address and dance together. Still in the works: The Coppelia Project, which is creating a small company of robot ballerinas (4) to learn and perform ballet dance movements. Inspired by the ballet “Coppelia” by Delibes, based on an earlier work by Hoffmann, Drake-Brockman shares that Curious Creatures symbolizes a milestone for the project. With three other half-completed ballerinas located in-studio, it’s the first time that Coppelia One has reached full expression. While the big-picture plan is to create a stage performance based on the project – for now, the artist is ready to fill a blank canvas

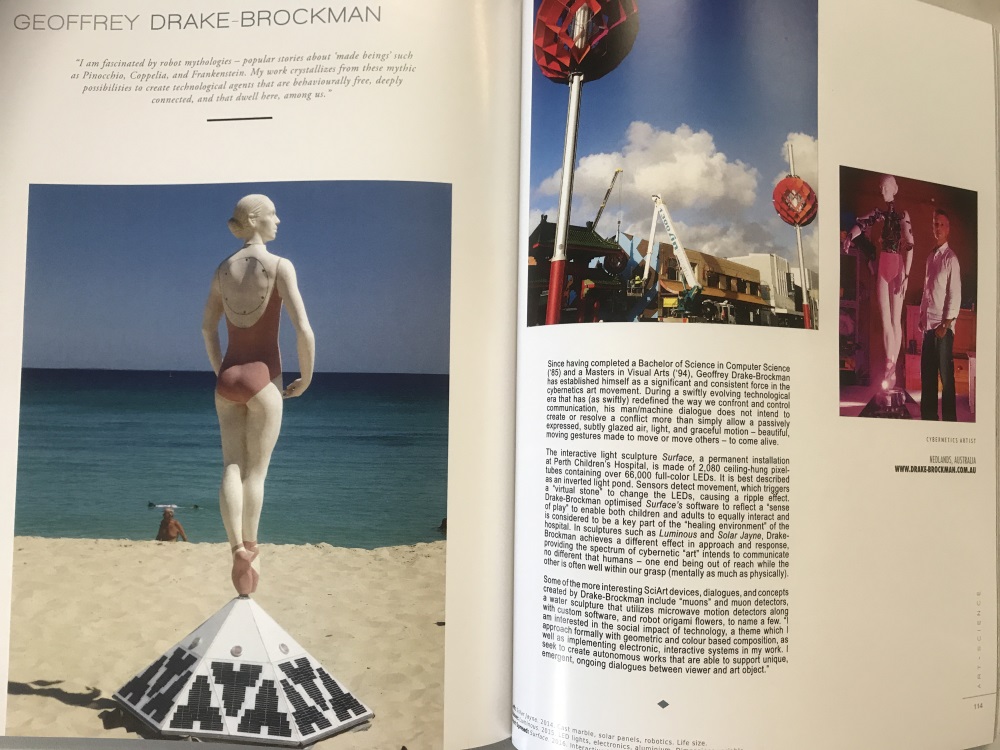

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - Cybernetics Artist

by EMILY Published: 11 Oct 2017

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - Cybernetics Artist

Mirror Beings - Robot Complexity, Myths, and Simulacra

by GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMANPublished: 3 Oct 2017

Mirror Beings - Robot Complexity, Myths, and Simulacra

Man, Machine, Viewer, Object: The work of cybernetics artist Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

by CARLY ZINDERMAN

Published: 28 June 2017

Man, Machine, Viewer, Object:

The work of cybernetics artist Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

Artist Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s expertise and vast

creativity belong to two niches that, when brought

together, seem to manifest unlimited possibility. He

combines the forces of computer programming and fine art,

commenting on both the human condition and, more directly,

viewer response, by exhibiting pieces that create an

environment and experience in and of themselves. Although

he once saw the fields of computation and art as

completely divergent, he has since begun to recognize

their ability to complement one another.

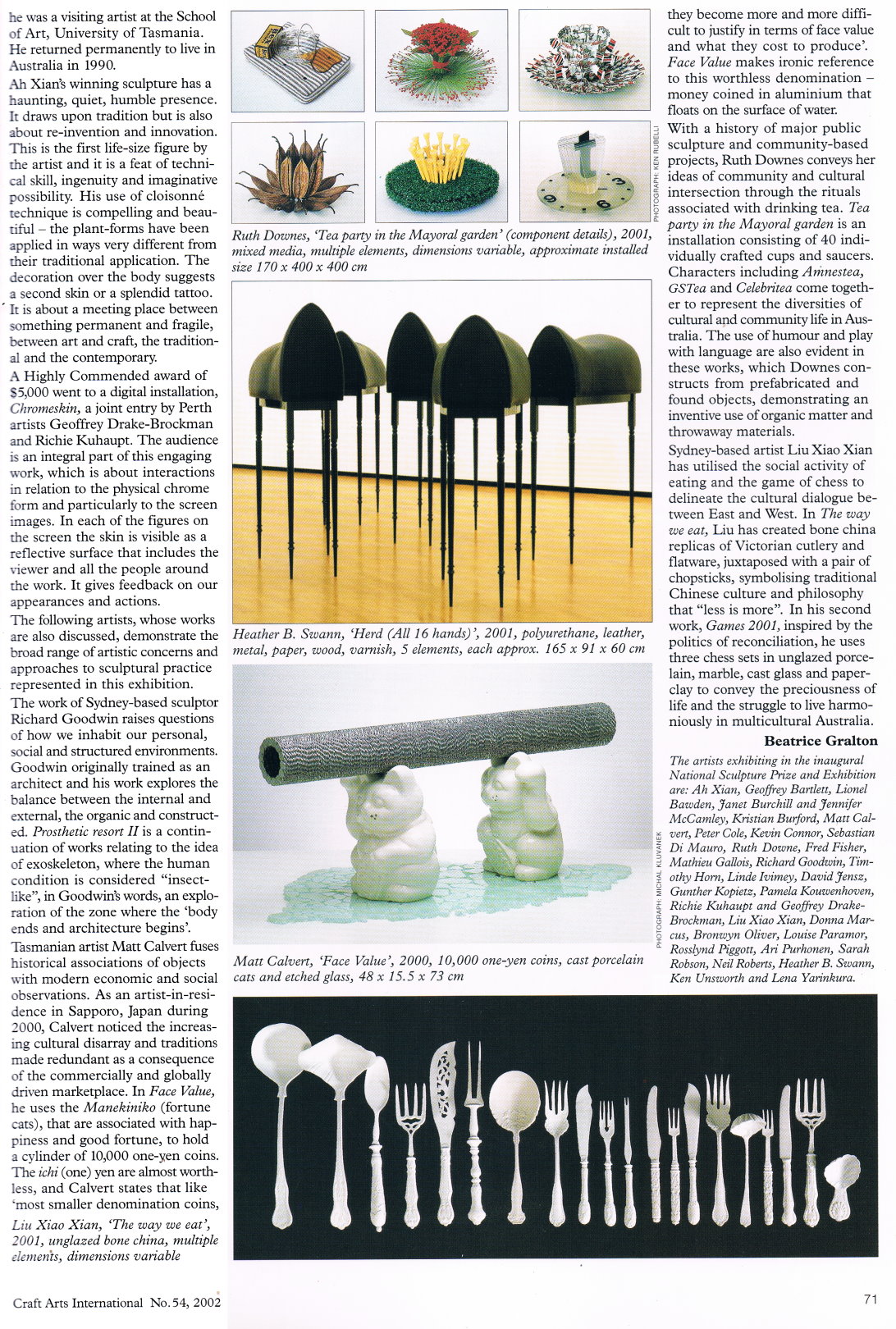

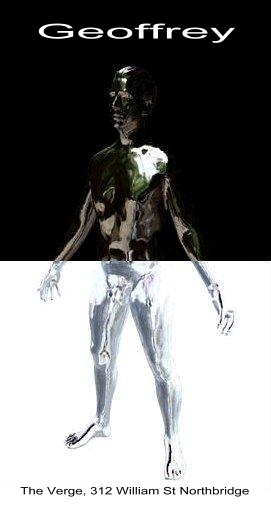

His first major piece was created in 2001, combining an

artistic vision with computational realization, and was

entitled Chromeskin(collab. R Kuhaupt). This piece – which

was shown at the National Gallery of Australia – consisted

of a chrome-plated sculpture of a human form, accompanied

closely by an animated digital rendering of the same form.

The relationship and tension created between these

physical and cyber territories have informed much of

Drake-Brockman’s work going forward, and can even be seen

as an important stepping stone in the history of digital

artwork.

While experimenting with several other light-, laser-,

cyber-, and sculpture-based works, Drake-Brockman

developed new artistic processes that paralleled the

rapidly advancing technology available to him. Soon came

Floribots, which debuted at the National Gallery of

Australia in 2005. As he puts it, “Floribotsuses

technology in a non-fetishistic way. It is colorful and

emotionally active, though its computational capability is

core to its expressive action.” This representation and

utilization of technology was important to Drake-Brockman

– he wasn’t interested in simply pushing technologies to

their limits as a spectacle of human achievement, but

rather using them in a sophisticated manner to demonstrate

the humanistic relationships they have come to facilitate.

The interactive installation showcases 128 robotic flowers

working both individually and collectively, reacting to

audience behavior and physical input, to explore the

realities of societal living – blooming, wilting, and

reblooming to simulate life’s endless narrative. It is

just one example of Drake-Brockman’s interest in pushing

boundaries as a multidisciplinary artist, exploring in

detail everything from the materials he chooses to his

selection of installation locations, which often go beyond

the gallery and into the public domain.

As a longtime cybernetics artist, Drake-Brockman is

strongly influenced by the theoretical basis of the art

form, dating all the way back to its origins in the 1940s

with mathematician Norbert Wiener, largely considered the

pioneer of cybernetics. “He foresaw many of the modern

applications of cybernetic technologies, even a possible

end of human labor with the introduction of machine

workers,” says Drake-Brockman. He goes on to explain how

the progression of cybernetics came about in this modern

age of technology:

“The explosion in the availability of cybernetic systems

in our daily lives has come about through the ready

availability of inexpensive digital devices. I'm

interested in artistic interactions that are open-ended,

and I need cybernetics for that. I avoid playback loops

and the use of standard pallet-effects in my work,

preferring to work with hand-coded software to define

multiple levels of abstraction between an input stream and

a set of outputs. These levels of abstraction act on

one-another to create the results that the viewer

experiences. The software - with the multiple feedbacks

acting in parallel - along with the connected sensors and

output devices, are the first level of cybernetics in my

work. The second level of cybernetics I'm interested in

spans the broader system, including human participants,

who add more layers of abstraction and parallelism to the

overall construct.”

In addition to cybernetics, Drake-Brockman also draws from

“robot mythologies,” such as Pinocchioand Coppelia. His

work capitalizes on the human/robot interactions—romantic

or otherwise—that have been utilized throughout history,

including Frankenstein, Pygmalion and the even the film

Her.

Drake-Brockman’s thoughts on the future of

technology-infused artwork are different from what you

might expect. As he explains, technology has long been a

medium of all forms of art:

“All art is technology. Even what we think of as

traditional media – like bronze sculpture, printmaking, or

film-based photography – use technologies that, at their

time of introduction, were radical and

civilization-changing. Artists will always use and adapt

technologies of the day. However, when an artist

deploys a technology, they invert the regular idea of it

having a ‘use’ or ‘function’ at the service of the

prevailing social order, and instead, it becomes an agent

that can actually act on the social order.”

At present, Drake-Brockman has three major pieces on

exhibition at the Morris Museum in New Jersey. Each

individual piece took years to create, collectively

showcasing an ongoing cycle that began nearly twenty years

ago. This exhibition is the single largest gathering of

the artist’s major works in one show at one time. In

addition to Floribots, there are two new figurative works

in the show, both modeled on a real ballerina named Jayne

Smeulders. One of these pieces is a full-sized, sculptural

dancing robot titled Coppelia One; the other is an

augmented reality installation titled Parallax Dancer.

Both interpretations of Smeulders, physical and virtual,

are able to interact with their audience in unique ways.

Drake-Brockman explains that Coppelia One is the first of

a planned sequence of four identical Coppelia robots. This

initial figure acts almost like a life-sized music-box

ballerina, spinning around en pointe and responding

according to the angle upon which audiences view her. This

is made possible thanks to four motion detectors, allowing

the robot to rotate towards her viewer and perform a

dance. Parallax Dancer, on the other hand, utilizes six

machine vision cameras, allowing a “parallax-corrected,

life-size, 3D dancing animation” to be displayed on the

cuboid of screens that make up the installation. The

artist muses, “In a way they are twins. They are installed

next to each other in the gallery, and the audience can

move between them, comparing two very different

technological approaches to essentially the same

representational theme.”

For Drake-Brockman, this exhibition marks a milestone and

has created a space for him to begin new long-term

projects including some interactive public art commissions

that are currently in the works. He recently presented a

keynote artist talk during this year’s AutomataCon, and

will have a booth at the upcoming AIA Conference on

Architecture taking place June 21-23 in New York City.

Eventually, Drake-Brockman plans to return to more human

themes, including the one that started it all: Eve and the

Apple. Until then, you can keep up with Drake-Brockman at

http://www.drake-brockman.com.au/.

CREATED BEINGS: FROM COMMONPLACE MOTIFS TO ROBOT MYTHS AND SIMULACRA

by GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMANPublished: October 2015

Created Beings: From Commonplace Motifs to Robot Myths and Simulacra

Abstract— A commonplace object becomes the basis for an autonomous artwork called Floribots. The work exhibits novel movement patterns that are highly engaging to its audience - leading the author to posit the phenomenon of emergence to explain unanticipated artwork behavior. The limits of this explanation are mapped by creating a series of autonomous artworks of varying levels of complexity. A synthesis around the nature of created beings is extended with reference to anthropomorphism, robot mythology, and simulacra.Keywords— robot; interaction; emergence; automatous; artwork; anthropomorphism; mythology

I. COMMONPLACE TO COSMIC

This paper traces a speculative journey by the author investigating the nature of “created beings” – machines that we make as reflections of ourselves - looking at their interactions with us, and potentially with others. Along the way, a series of postulations are articulated to explain the mechanisms that allow such beings to come into existence and cause them to act in interesting ways. These postulations become the basis for a body of fully-resolved automatous artworks - each of which is described and analyzed in terms of a developing explanatory synthesis.

...

CYBERWORLDS PARTICIPATION REPORT

by KAZUO SASAKIPublished: 13 November 2015

Cyberworlds Participation Report

This is the final report of CYBERWORLDS 2015. This time, I would like to introduce Jeffrey's work that won the "Best Paper Award" with our team. With your consent, you will also be able to see photos of the work. I am impressed with only very exciting and novel works.First of all, it is this flower garden, each of which is an independent sensor unit. The flowers planted in the flower pots are actually made of "Japanese origami". This installation senses the movement of people passing by and starts moving as a switch. And once they start to move, the units next to each other will sense the movement and move, so the “flower movement” will spread more and more. it's interesting. Will someday be able to do an installation in Japan?

...

(Translated from Japanese)

HEADSPACE: (GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN)

by EMILIANO CAUSA Published: 2014

Headspace: (Geoffrey Drake-Brockman)

Headspace is an array of 256 motorized rods. Each rod is able to extrude about 400 mm. It is an interactive kinetic sculpture with four motion detectors capable of detecting human presence. He settled permanently at the Christ Church Grammar School in Perth, Western Australia.The system is loaded with 3D scan data based on the faces of more than 700 school-age children, the bar matrix is capable of assuming face shapes and making geometric transitions.

This kinetic work is closely linked to generative art, since in the same way as Van Weeghel's work, it has a high level of automation in the generation of the variable topography of its surface, defining different compositions or reliefs that vary by decisions taken for the system and for the interaction of the users.

The movement of the rods is constant and the transitions that integrate the representations of the scanned forms endow the work with an organic behavior and always different from the previous states.

(Translated from Spanish)

MULTIMEDIA PERFORMANCE - VIRTUAL THEATRE

by ROSEMARY KLICH & EDWARD SCHEERPublished: 2015

Virtual Theatre

...Australian sculptor Geoffrey Drake-Brockman created an unusual example of a responsive artwork functioning as an 'interactive environment'. Floribots (2005) is a play on 'flowerpots' which presents 128 computer-controlled robot origami flowers that cover 35 metres of gallery space and react as a collective organism to the movements of the viewers. Each mechanical flower is able telescopically to 'grow' up to a metre high and fold out from its origi-nal bud-state into an open bloom, then shrink and retract into its dormant state. The behaviour of the flowerbed senses and reflects the behaviour and movement of the viewer, flowing from chaotic movement to organised wave-like patterns, with the 'hive mind' of the Floribot controlling the transition between these states. The Floribots function only in response to the actions of the viewer; once the viewer has become familiar with the programmed responses of the Floribot-bed, they are able to choreograph complex movement sequences. It becomes a performance, and as the viewer learns the rules of engagement and their skill level increases, their level of creative interaction becomes more sophisticated.

...

Where art and robotics collide: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

Interview with CLAIRE NICHOLS

Published: 14 May 2016

Where art and robotics collide: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

His solar-powered spinning ballerina, Solar Jayne, pirouettes at the touch of a button. The giant yellow archway, Counter, literally counts viewers as they walk through the piece.

Drake-Brockman uses his expertise in computer science and visual art to create his unique interactive pieces, and says beneath the candy-bright colours, there's a touch of gothic horror about the works.

'Those wonderful stories of Frankenstein and Dracula, they inhabit my work at some level,' he says.

Art of the Future

Produced by Published: 3 November 2016

Art of the Future: These Interactive Sculptures Respond to You

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman makes cybernetic sculptures that appear to come alive with human interaction. Using his background as a computer programmer, this Australian artist makes work that moves, twists and even changes colors in response to a viewer’s movement. For Brockman, it’s this conversation between his art and the audience that makes his work special and engaging in a whole new way.Through the looking glass

by WILLIAM YEOMAN

Published: 30 April 2016

Through the looking glass

But how many have seen Drake-Brockman’s futuristic, technology-driven work as a prime example of Shakespeare’s idea of art holding a mirror up to nature? Now, in his first commercial exhibition in over a decade, the man who initially studied computer science because he believed art couldn’t be taught (he soon saw the error of his ways and attended art school) presents Looking Glass, a major survey of Drake-Brockman’s work across multiple media including sculpture, painting and installation.

“Having a a gallery exhibition like this allows me to put the full continuum of my practice on show, and hopefully create some links that people can see between the public art and the studio art, Drake-Brockman says.

Among the works on display is a spectacular new series of circular, square and triangular Portals which incorporate mirrors while echoing the art of hard-edge abstraction. “A looking glass is an archaic name for a mirror,” Drake-Brockman says. “The ‘paintings’ are mirrors. Yes, art is automatically a mirror. But putting a real mirror in there forces the issue. It implicates the viewer directly and quotes them back to themselves, if you will.” Perfect for the age of the selfie, one might say.

The exhibition’s title also recalls Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking Glass. But the connotations are more complex than that. “Mirrors do lots of wonderful things,” Brockman says. “They can be portals to different realities, like the one Alice passes through. They can recall a futuristic super-technology world and the super-reflective chromium surfaces you always see in science-fiction movies.”

Technology, of course, is another main theme in Drake-Brockman’s work. “I’m intensley interested in technology and it’s always woven into my work, either literally in terms of electronics or conceptually in terms of the direction that the work suggests,” he says. Given the swift changes in science and technology over the decades Drake-Brockman has been making art, it seems natural to assume his work would have evolved with it. That, however, inverts the reality, much as a mirror can.

“The evolution of technology doesn’t necessarily change the conceptual space because that can be in advance of what’s currently technologically possible,” Drake Brockman explains. “Just think of science fiction authors such as Arthur C. Clarke, who predicted geostationary sattelites long before they became a reality. Certainly, advancing technologies are very noticeable when you’re going about implementing a particular technological trick. Things which were once difficult and expensive to achieve become cheap and easy. “But the conceptual range of possibilities doesn’t change.”

And what of the different possibilities afforded by public art? “All my works are thematically linked,” Drake-Brockman says. “What the public art does is provide an opportunity to realise those themes on a larger scale. It also provides a large audience.”

Different again is the kind of audience one gets by exhibiting in Sculpture by the Sea. “You put a sculpture in front of 100, 000 people, right in the middle of their domain: that’s non-public art with high visibility,” he says. “Basically, the more people interact with my work, the more value I get out of watching it and seeing the possibilities.”

Looking Glass runs at Linton & Kay Galleries, 137 St Georges Terrace, from Monday-May 22. Picture: Iain Gillespie

Geoffrey DRAKE-BROCKMAN, Readwrite (2014)

by HERVE-ARMAND BECHY

Published: June 2015

Geoffrey DRAKE-BROCKMAN, Readwrite (2014)

Readwrite is a cosmic-ray activated robotic artwork by

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, located in Perth, Australia.

Readwrite is a cosmic-ray activated robotic artwork by

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, located in Perth, Australia.Readwrite is installed on the NEXTDC Data Centre in Malaga, Perth, Western Australia. It is 10m long and features a grid of 24 pneumatically-actuated 1.4m wide diamond-shaped flipping elements.

Dance sequences on Readwrite are triggered by charged "Muon" particles. Muons are terrestrial Cosmic Rays generated in the upper atmosphere by interactions with high-energy particles from distant supernovae and black holes in active galactic nuclei. Readwrite has four Muon detectors, mounted at its corners. When a Cosmic Ray hits a detector, a wave motion sequence begins from that point. Other choreographed behaviours occur depending on the frequency and spatial distribution of the Muon flux. Readwrite only reacts to the rarest incoming Muons - those that are travelling parallel to the Earth’s surface.

Readwrite was installed in January 2014 and has been in near-constant motion since. It may be the largest terrestrial automata activated by stimuli of extra-galactic origin.

The Readwrite control algorithm is a modified version of the code from Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s earlier work Floribots, and thus retains elements of the emotional modes of that work (bored, excited, etc.) - which were originally modelled on the behaviour of the Artist’s sons at toddler age.

Readwrite is the latest in a series of robotic works by Drake-Brockman that explore the potential for emergence in relationships with machines. The Artist notes that his background in Computer Science informs his project to create automata, which he explains further in his 2013 TEDx talk, for details see www.drake-brockman.com.au

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - human/robotic nature

by JULIA BUNTAINE

Published: February 2015

GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN - human/robotic nature

Geoffrey

Drake-Brockman’s art addresses the social impact of

technology through geometric and color-based composition,

as well as electronic interactive systems. He seeks to

create autonomous works that support open-ended dialogues

between viewer and art object. Socio-historically, he

views himself as a technological determinist. He utilizes

methods from computer science and designs his projects in

terms of state mechanics, computability, and orders of

complexity.

Geoffrey

Drake-Brockman’s art addresses the social impact of

technology through geometric and color-based composition,

as well as electronic interactive systems. He seeks to

create autonomous works that support open-ended dialogues

between viewer and art object. Socio-historically, he

views himself as a technological determinist. He utilizes

methods from computer science and designs his projects in

terms of state mechanics, computability, and orders of

complexity.Q&A Interview:

JB [Julia Buntaine, Feature Member Editor @ASCI]: Your work is characterized by the incorporation of robotic technologies to create interactive installations that deal with subjects such as nature, learning, behavior, and the body. When did you begin to pair robotics and these subjects, and why?

GDB: [Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, artist]: I was exploring possibilities for working with 'chatterbox' origami forms back in 2000. I liked the chatterbox as it's a simple childish toy that anyone can make, but it has some quite complex geometry in terms of its range of spatial transitions, and carries interesting cultural overtones. For example, it can be used as a fortuneteller and I wanted to activate this culturally charged form with technology so it could interact with an exhibition audience. I had a clear notion that the artwork should 'reach out' to communicate with its audience in the 'real world', and robotics was a way to achieve this. I experimented with adding robotic activation to the chatterbox, and found myself drawn down a path that led to the creation of a work called Floribots.

JB: In your piece

"Coppelia Project," you speak to both the limits of

humanity and robotics by creating robotic dancers that

imitate human dancers, based on the original "Coppelia"

choreography of a dancer playing robot. Can you talk a bit

about the interactive elements of this work, and reactions

from your viewers?

JB: In your piece

"Coppelia Project," you speak to both the limits of

humanity and robotics by creating robotic dancers that

imitate human dancers, based on the original "Coppelia"

choreography of a dancer playing robot. Can you talk a bit

about the interactive elements of this work, and reactions

from your viewers?GDB: The four Coppelia Project ballerina robots are designed to interact with each other, as well as with their human audience. The robots communicate with each other over a wireless network, and can share cybernetic ‘intentions’ that way. In contrast, their sensory connection with the human audience is more rudimentary. Each robot has four infrared motion detectors that allows her to detect human activity levels, but any subtlety of the 'state' of the audience has to be inferred by her software. Interaction with humans is further complicated in this work because these robots are anthropomorphic, and are based on a body-mold of the wonderful ballet dancer Jayne Smeulders. The 'uncanny valley' is deliberately evoked, and people are attracted and repelled at the same time. In presenting this robotic piece alongside human ballet dancers, questions are raised in the mind of the audience, such as: are robots going to replace ballerinas? and can a robot ever be truly graceful?

JB: In Floribots you created an installation of robotic flowers, each imitating the cycle of life in growing and blooming. Acting as a unified field of flowers, the audience influences the 'hive mind' behavior which adapts itself over time. Having only given this installation simple programming capable of adaptive learning, what surprised you when it was finally up and running? Did it have any behaviors you didn't expect?

GDB: I was rushing to finish Floribots before the deadline for its first exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia. I only had a few days to finish writing the software at the end of the process, so it wasn't until the exhibition opened that I actually saw Floribots fully realized for the first time. The installation was a matrix of 128 robotic origami flowerpots with over 4,000 moving parts. The thing that struck me initially was the sound. When the robot flowers in Floribots transition from bud to bloom, they make a soft 'whoppp' sound, but when all of them are rhythmically opening and closing, the sound composition becomes surprisingly intense. As the exhibition progressed, what really caught my attention was a whole range of unanticipated artwork behaviors. Floribots was programmed to adapt its behavior over time, reacting to audience input in a limited number of ways. However, as the author of Floribots' software, I soon saw autonomous behaviors manifest that I could have sworn were not possible. After a while, I came to regard these behaviors as 'emergent' - developing from potential that's inherent in the complexity of the artwork-audience interaction system itself.

Images:

Floribots installation by Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, 2005, origami, lacquered hardboard, robotics, 8m x 4m x 1.5m

The Coppelia Project by Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, 2015, robotics, dimensions variable

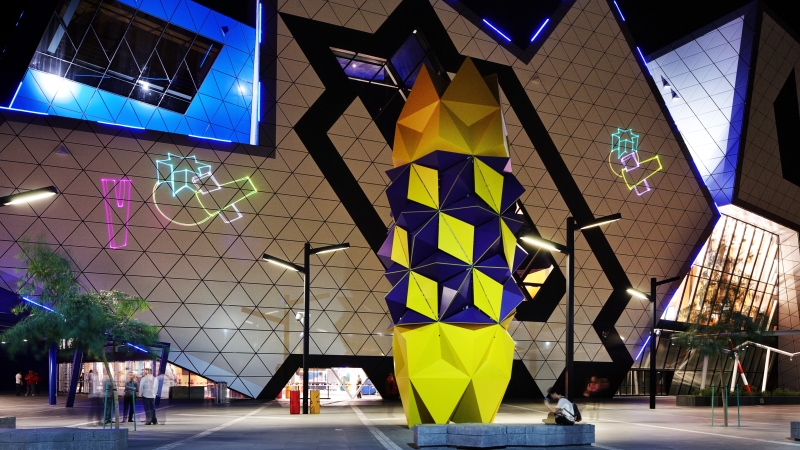

Totem by Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, 2012, aluminum, steel, robotics, laser projectors, 3m x 3m x 11m

GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN - The Coppelia Project

Published: January 2015

GEOFFREY

DRAKE-BROCKMAN - The Coppelia Project

GEOFFREY

DRAKE-BROCKMAN - The Coppelia Project

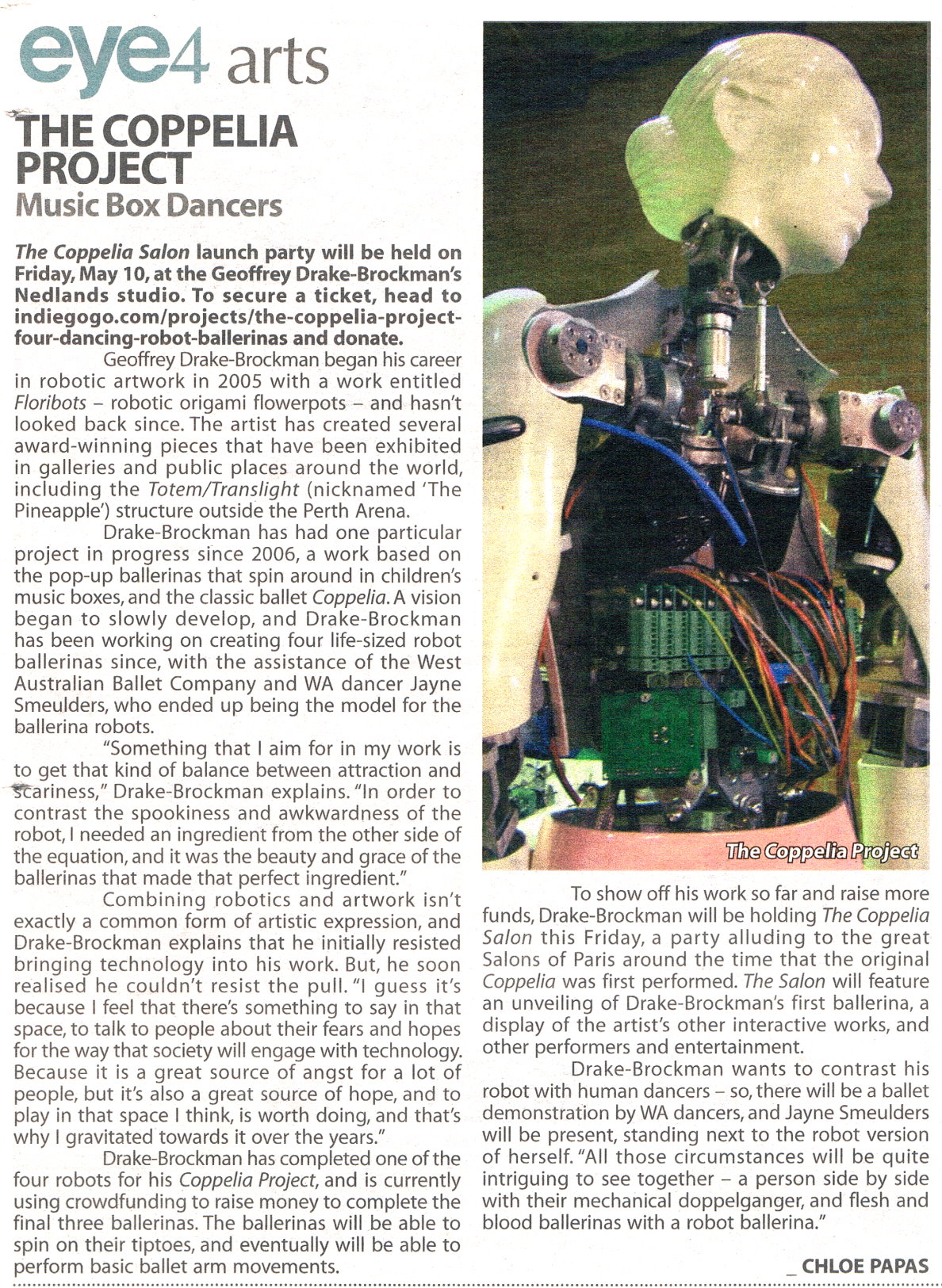

The Coppelia Project is inspired by the story about

a clockwork girl from the 1870 ballet ‘Coppelia’ by

Saint-Léon, Nuitter, and Delibes, based on a story by

Hoffmann. It also draws the commonplace metaphor of

clockwork music boxes, with the little ballerinas that pop

up and rotate in front of a mirror when you open the lid.

Coppelia is part of the traditional classical ballet

repertoire and is performed frequently by ballet companies

around the world. It belongs to a small group of enduring

stories in Western Culture that directly address the

limits of humanity when confronted by our creations. The

Coppelia story is unusual in approaching this theme

through love and attraction, rather than horror and

revulsion, as emphasised by Mary Shelly in ‘Frankenstein’.

The Coppelia story deals with some of the issues at the

edge of humanity; machines interchangeable with persons,

love and attraction confused at this boundary.The Coppelia Project has been assisted by the Australia Council for the Arts, Arts WA, The West Australian Ballet, and the many generous contributors to its Idiegogo crowd-funding campaign. See the Sponsors page for details.

The artist says; ‘I have always been intrigued when watching Coppelia being performed by a ballet company – one always sees the most beautiful and graceful ballerina “hamming it up” to move like a clunky robot girl. I decided to add another layer of irony to the situation my making a robot to imitate the dancer who is imitating the robot… Of course, robots are manufactured goods, not people, so I had to make four. From the images below, you may note an overtone of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film masterpiece “Metropolis” and its heroine “Maria”. I am interested in such stories about robots and automata that crossover into the human realm. The Coppelia Project is about the boundary conditions of humanity as it confronts is technological alter ego. The robots are robotic “blanks” that are energised by their programming to mimic the elegant movements of human dancers, but are imperfect in their attempts at human grace.’

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s goal is to create automata – interactive, self-determined, expressive machines – that once set free, operate to independently explore issues at the edge of humanity; machines interchangeable with persons, aspects of political accountability, love, and attraction in flux at this boundary. Through his practice Geoffrey combines his interest in gothic horror themes, especially Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein story, with the politics of social determination through technology, and commonplace, accessible metaphors such as clockwork music boxes, flower-pots, doorways, simple origami shapes, and portrait relief.

The Coppelia Project robots are specially designed to learn and perform the movements of classical ballet. They can spin “en pointe”, move their waists, arms and head. They cannot walk and their hands do not have grippers to pick things up. They are optimised only as ballerina robots. The Coppelia Project robots are taught ballet movements by having their arms, head, and torso physically moved through a ballet sequence by our ballerina trainer. An on-board computer captures the motion so it can replay it later – in various dance move combinations.

The Creation of the Coppelia Robots is the cumulation of an extensive research and development exercise undertaken with the assistance of Jayne Smeulders of the West Australian Ballet. Jayne was the model for the robots and assisted the artist while researching the requirements for ballerina form and movement.

The Coppelia Project is the ultimate outcome of a series of increasingly complex robotics projects, including “Floribots” (2005) “Headspace” (2010) and “Totem” (2012). Two other ballerina related projects have also taken place alongside the Coppelia Project, one is “Parallax Dancer” – a 3D virtual dance installation, and the other is “Cockwork Jayne” – a simple windup version of the ballerina robot. More detail on these projects is available at the artists main web site.

Record-breaking numbers and heights at Sculpture by the Sea

by LUCY CORMACK

Published: 24 October 2014

Record-breaking numbers and heights at Sculpture by the Sea

As the 2014 Sculpture by the Sea exhibition celebrates the 1000th artist to have featured in the event, one exhibiting artist is hoping to

set a record of his own. He just needs the help of exhibition goers to pass through the arch of his artwork 999,999,999 times.

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman's Counter does exactly what it says on the box. Each time someone walks through its infrared beam, the solar-powered counter goes up by one. Now showing for the fourth time in its fourth location across the world, he is hoping to well and truly pass the record of 288,601 in Aarhus, Denmark, to one less than a billion, whereupon it will tick back to zero.

"The positive is to participate in the social order, to stand up and be counted, to make your life count. The negative is just to be reduced by a machine to a number in the database. People can make the choice to be counted or not." Counter is just one of 109 sculptures from 16 countries now perched along the coast from Tamarama to Bondi for the 18th annual Sculpture by the Sea.

Image: Geoffrey Drake-Brockman: one in 999,999,999. Photo: by Steven Siewert

ART PUBLIC, France

Geoffrey DRAKE-BROCKMAN, Totem. Perth (Australia)

by HERVE-ARMAND BECHY

Published: November 2013

At 11-metres tall, with 108 reconfigurable petals and three laser projectors, Totem is one of the world’s largest and most complex interactive artworks. The work responds to pedestrian movements and is sensitive to environmental conditions.

Totem was commissioned in November 2012 by the Government of Western Australia for the pedestrian plaza adjacent to the Perth Arena entertainment stadium.

The work incorporates a laser projection artwork titled "Translight" that creates nightly a variable “geometric narrative” light composition on the Eastern wall of the Arena. The kinetic responses of Totem vary depending on pedestrian activity-levels, as sensed via its six microwave motion detectors. The work can assume regular, symmetric configurations as well as entering chaotic transitional states.

Totem has been nicknamed "The Pineapple" by the people of Perth. It is the latest in a series of robotic artworks by Drake-Brockman that explore the potential for emergence in relationships between machines and people.The Artist notes that his background in Computer Science informs his project to create automata, which he explains further at his recent TEDx talk, for details see:

http://www.drake-brockman.com.au/TEDx.html

X-PRESS MAGAZINE

EYE4 ARTS

THE COPPELIA PROJECT - MUSIC BOX DANCERS

By CHLOE PAPAS

Published: 8 may 2013

TEDx PERTH

Created Beings

by GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN

Published: December 2012

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - Created Beings

TEDx Perth December 2012, Talk length: 14:53

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - Robot MakerGeoffrey is a Perth-based artist specialising in robotics, lasers, and optical interactive installations. Geoffrey studied Computer Science at The University of Western Australia before completing a master’s degree in Visual Arts at Curtin University. He has been exhibiting since 1986 with shows in Perth, Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Singapore, New York and London. His most recent solo exhibition was in 2010, when he installed his robotic work Floribots at the Singapore Art Museum.

Geoffrey has also shown work at the National Gallery of Australia and participated in the Helen Lempriere National Sculpture Award, The Biennale of Electronic Arts Perth and Sculpture by the Sea – in Bondi, Cottesloe, and Aarhus, Denmark. Geoffrey has completed a number of public art commissions including the laser-based work Transfiction (Canberra) and the robotic sculpture Totem at the new Perth Arena.

|

|

THE STRAIGHTS TIMES, Singapore

Flower Power

By NEO XIAOBIN

Published: 12 May 2010

REALTIME, Sydney, Australia

Sculpted: conscience and consciousness

by ZSUZANNA SOBOSLAY

Published: issue #70 Dec-Jan 2005 pg. 49

Sculpted: conscience and

consciousness :

Zsuzsanna Soboslay on the National Sculpture Prize

Ahh, sculpture competitions: much better represented now in Australia than they used to be. By the sea (Sydney), in the park (Werribee), or as here, held within walls. Much more space than before; this, the third Gallery event, seems to have gained kudos, been allowed more space, attracted higher calibre submissions. Newcomers beside old hands. Fewer mistakes.

The first mistake: squashing them in. In the first two National Sculpture Prize exhibitions (2001 and 2003), I actually missed site-specificity: pined for installations in grasses and on plains, Richard Long-type spirals of stone and sand. This time, I’m really glad I’m in this building here. The placing of works is really right: the art is given space. Sculpture is BIG, even when small. Even hanging on a wall, sculpture works out into space, asking questions wider than its dimensions.

The second: I’m not sure it’s a mistake as such, but the previous 2 exhibitions had phenomenal prize-winners, and a lot of work that was very thin. Technique in this year’s entries is incredibly strong: from the very senior Bert Flugelman’s understanding of the effect of light on polished and ground steel, to Drake-Brockman’s programming of motions and rhythms between elements across a large field, to the various manipulations of plastics, tape and paper, foams and foil, optics and animation. These pieces are allowed their worlds. I deeply understand Flugelman’s phrase on the way art reflects “what one might euphemistically call the ‘real world’.” Art also lives; it is. Even reflections on death (Glen Clarke’s Hanoi; Mel Coates’s underwater video of a drowning parachutist) create a space that lives.

Sculpture, more than painting, dissects dimensions in space, and in that dissection time separates: whose is this body Charles Robb reveals, the classic portrait ‘bust’ against the wall, popping a substance through its orifices, a second revealing its insides (heart and lungs)? The best works dissect the forms we think we move with and through in the world.

Alisdair Macintyre draws together hundreds of works of art and art sites he would like to have visited from several continents, miniaturised into one “theme park” which holds them all. As with the dance of the mechanoid Floribots, and Ian Howard’s enormous scrap-yard of life experiences, adults and children alike are held in thrall.

Works in this exhibition spiral, hide, hollow, store, map and conceal. They spread, climb, hover, fold into myriad cells. They engage in damage (what remains after war, or the sufferings of the ecosystem), and hope (what of both art and life survive). It is little surprise Glen Clarke’s Hanoi #2 wins the prize, as it engages in nearly all of these. There is a conscience and a consciousness in these works. The exhibition has a brightness I haven’t seen in years.

National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition, 2005, National Gallery of Australia.

THE WEST AUSTRALIAN

A dip into illusion

by RIC SPENCER

Published: 10 February 2007

PERTH INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman - Floribots

by Dr BENJAMIN JOEL

Published: 2007

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman’s first degree was devoted to the rigorous study of computer science. Whereas this training has had an acknowledged effect upon his prodigious intellection, reflected in the organisational acumen and clear thought that one might predict, it has also been an implicit factor in the orientation of his developing imagination. What piques his intrigue most keenly these days are the philosophical connotations in ‘the social realities consequent to the technologies of simulation’(1) in which (as a professional programmer – an aspect of his ‘other’ life) he sees himself implicated.

In a perfectly viable sense Floribots itself, presents as a social organism, simulating behaviours that are those of both an individual and a colony. By way of some complex feedback cybernetics, a number of absorbing social realities arise in the interaction that an audience is able to experience with the work.

Floribots operates at so many levels and in such multiple sets that it’s tempting to start out with a list of the referents that come immediately to mind. But I’ll resist for now, and in any case the work’s effect is quite different in varying contexts and at different times. Just over a year ago Drake-Brockman easily won the People’s Choice Award at the National Sculpture Prize in Canberra with this work. With its cross referential delights for so many viewers, this comes as no surprise. Its breadth of appeal has already covered a public ranging from the hard bitten art critical, to the simply art loving. Today and here, Floribots is fresh once more and creating a new fuss for a new audience

As with any worthwhile artwork, sustained viewing is rewarded, especially if you are to experience anything like the full range of sequences Floribots can display. If you spend enough time observing and being observed by this odd entity, your own gamut of potential associations and individual linkages with the work, your own readings of Floribots and its allusions will mount, as will, therefore, the satisfaction you derive from the interaction.

How does he do it? Geoffrey Drake-Brockman has regularly welcomed highly specialised procedural problems that might arrest the progress of any other artist. Solving problems in one field requires contextual knowledge in those adjacent. In order to address his self-set briefs and develop his vision, Drake-Brockman has developed an enviable expertise in, and in some cases broken new ground for technologies as diverse as… chrome plating (including that of plastics), various forms of electrical and electronic engineering, high-end software systems, systems analysis, casting, plastics chemistry, optics and laser engineering. He has acquired great proficiency in painting, colour theory, contemporary art and literary theory, if not (though I wouldn’t bet on it)… astrophysics, quantum mechanics and neurosurgery.

In the hands of an alert, appropriately tuned and open minded artist, the narratives underpinning prognostications about human/machine relations, the dreams of science and the implications of scientific abstractions, become an endless stream of fruitful stimuli and restless production. As has usually been the case with his extraordinary artistic enterprises, bringing Floribots to life entailed addressing specific and extraordinary technical challenges. The artist elaborates:

I like figuring out how to get the technical process to work - to make reality match the vision. However, it’s the idea, the 'vision' that comes first and it’s a matter of working through the technical problems to realize it. It intrigues me though that, usually, there is a way, somehow, of getting the technical stuff to behave the way I want it to. I seldom have to give up because something is just impossible. Like chrome plating over plastic, getting the mixture right for cast marble, de-bugging electronics, or finding a way for origami to operate with robotics; the process can be tricky but it can be done if you're patient and careful. For technical stuff though, I mainly like getting something new to work, to match the vision, rather than exploring the possibilities of a particular medium. I like to think that I don't fetishize the technology itself and that I'm not process driven. There is an aspect to well implemented technology that can attract people's attention though, that can act as a 'hook', and I appreciate the power of that. (2)

Technology may not be a fetish for this artist, but it seems to me that it is a prod. Its effect is to provoke the author but also to provide a subscept signifier along with a unique experience for the audience. For Drake-Brockman it must remain intrinsic, sexy but seamless, transactional but transparent. If he opts for the tricky technology entailed in chrome plating non metallic surfaces for instance, as he has in some earlier works, it’s because:

…chrome is interactivity itself. It reflects. Usually it reflects back a view of the viewer. I'm into chrome and equivalent mirror-reflective surfaces like polished stainless steel for practical reasons - they can pack such massive processing power, in terms of receiving and processing visual information, all from a completely 'passive' surface. Chrome is a cyberpunk signifier. Its been set up culturally in movies like Terminator II and The Matrix and in the traditions of science fiction to equal slick, seamless, deep technology. I can hint at potentials like this with this material… Every Floribot has a reflective plate facing up to the viewer. I don't think anyone should be allowed to think they can get away clean; and the chrome helps to signal that. (3)

Always aroused by the possibilities of painting, Drake-Brockman has never foregone the expressive capacity of the surface in his pursuit of depth. Floribots is no exception to these fascinations. The artist is also intentionally mining a culture that includes what has been theorised if not colonised by Baudrillard, and has it in mind, that as with the use of chrome for instance:

…reflection will be more than mere appearances. It will involve an appearance of an appearance and simulacra will be multi-order: simulations of simulations of simulations. (4)

What then are the potentials at which he is hinting with mirror faced robotic origami?

As has been suggested above, for an artist there have always been innumerable multivalent conceptual prompts in science and technology, and increasingly this has been a contemporary truism. Western Australia not least, has its own Biennale of Electronic Arts (in which Drake-Brockman has been an exhibitor) as well as the art and science collaborative research laboratory SymbioticA. Where there are evident implications in social phenomena or for social models, these cues are arguably at their most motivating. The physics of wave motion provides in a single example a profusion of analogies for which neither art nor articulation needs hyperbole nor hyping. It is now canonical, that at the atomic scale all objects have both wave and particle nature. None the less, as is the case with the pulsing dynamics of massed human behaviour to which in part Floribots may allude, there remains, encouragingly, a great deal yet to be understood, defined or explained.

In its own scalar dimension Floribots exhibits both wave and particle behaviours and takes this analogy, among others, to spectacular limits and into intriguing outcomes. Floribots dances in waves. For me its contextual overtones also arch oddly from dance and pattern aesthetics into hypnosis, horticulture and horror movie culture. Floribots hints too at the controlling patterns of self-organisation that arise in cellular structures of any sort, biological, social or machine-based. Its chattering chorus asks disturbing questions like: What is a mind… or for that matter a hive-mind? Philip K. Dick wondered if androids dream of electric sheep. Floribots learns, it sleeps, it wakes. Does it dream?

Floribots comes hard on the heels of a string of Drake-Brockman projects (5), seen here in Perth, interstate or abroad. Soon to follow will be The Coppelia Project, ‘a culturally located vision, about automata and the boundaries of humanity’. (6)

Ben Joel

December 2006

1. Artist’s notes, December 2006

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. (some in partnership with his long time collaborator Richie Kuhaupt)

6. Artist’s notes, December 2006

ARTLINK

National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition 2005

By ELVIS RICHARDSON

Published: Vol 25 no 4, 2005

National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition

2005

..THE ARTIST'S CHRONICLE, Cover Article

Floribots and Laser Beams - the art of Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

By LYN DiCIERO

Published: Issue 105, November 2005

Floribots and Laser Beams - the art of Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

THE CANBERRA TIMES, Page 3

Winning Sculpture a Fresh Take on Flower Power

By HELEN MUSA

Published: 28 September 2005

Winning Sculpture a Fresh Take on Flower Power

THE CANBERRA TIMES, Page 3

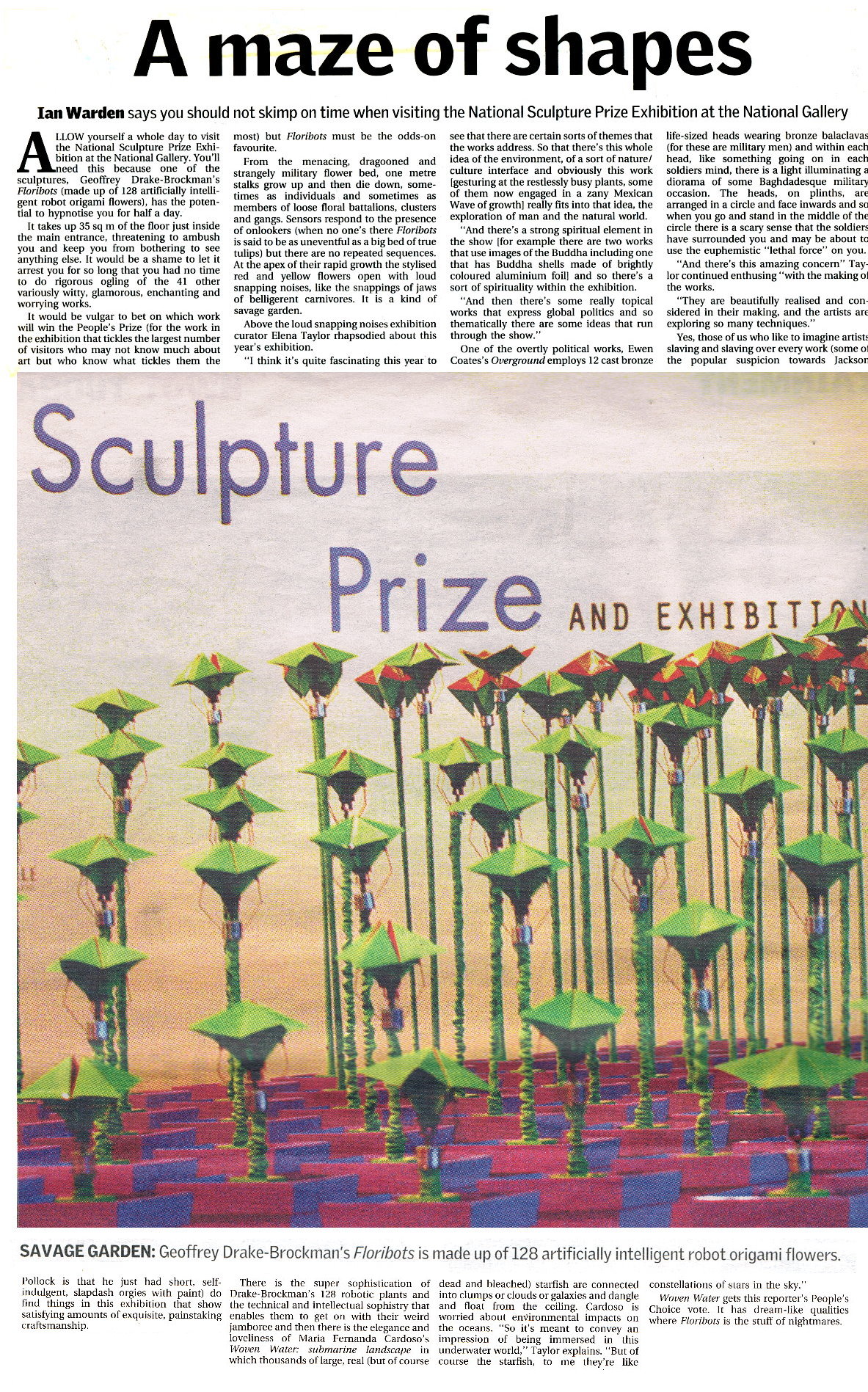

A maze of shapes

By IAN WARDEN

Published: 15 July 2005

Floribots - National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition - Artist's Statement

By GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN

Published: 2005

Essay from Catalogue of the National Sculpture Exhibition: - The National Gallery of Australia

The squared-off flowers of Floribots are well removed from the organic domain. They are mechanoids. However, in a way they too can play out the drama of life and death – bloom and wither – and they can show us other things as well...

Floribots consists of 128 computer-controlled robot origami flowers arranged in an eight-by-sixteen grid spread over thirty-five square metres of floor space. Each robot flower is able to extend telescopically from a rest condition to grow one metre vertically, then suddenly invert its origami ‘flower’ into an open bloom state. The unit can also re-contract back down into its latent state and refold its origami bloom back into the bud condition.

Floribots acts as an interactive collective organism with ‘hive mind’ characteristics. It is capable of sensing audience movement and of adapting its behaviours accordingly. It is a ‘field of flowers’ that dances in unison, with choreography provided by its embedded microcontroller. The flower matrix can exhibit complex wave propagation behaviours as well as describing responsive surface features and entering periods of chaotic motion. The Floribot mind is able to control transitions between these states and can ‘learn’ as it runs over time by acclimatising itself to an installation site and developing a particular set of behaviour preferences.

Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, 2005

METIS - A FESTIVAL OF SCIENCE AND ART

Laserwrap - Catalogue Essay for Metis

By BEC DEAN

Published: 2004

METIS

Essay from Catalogue: Metis – A Festival of Science and Art - Australian Capital Territory

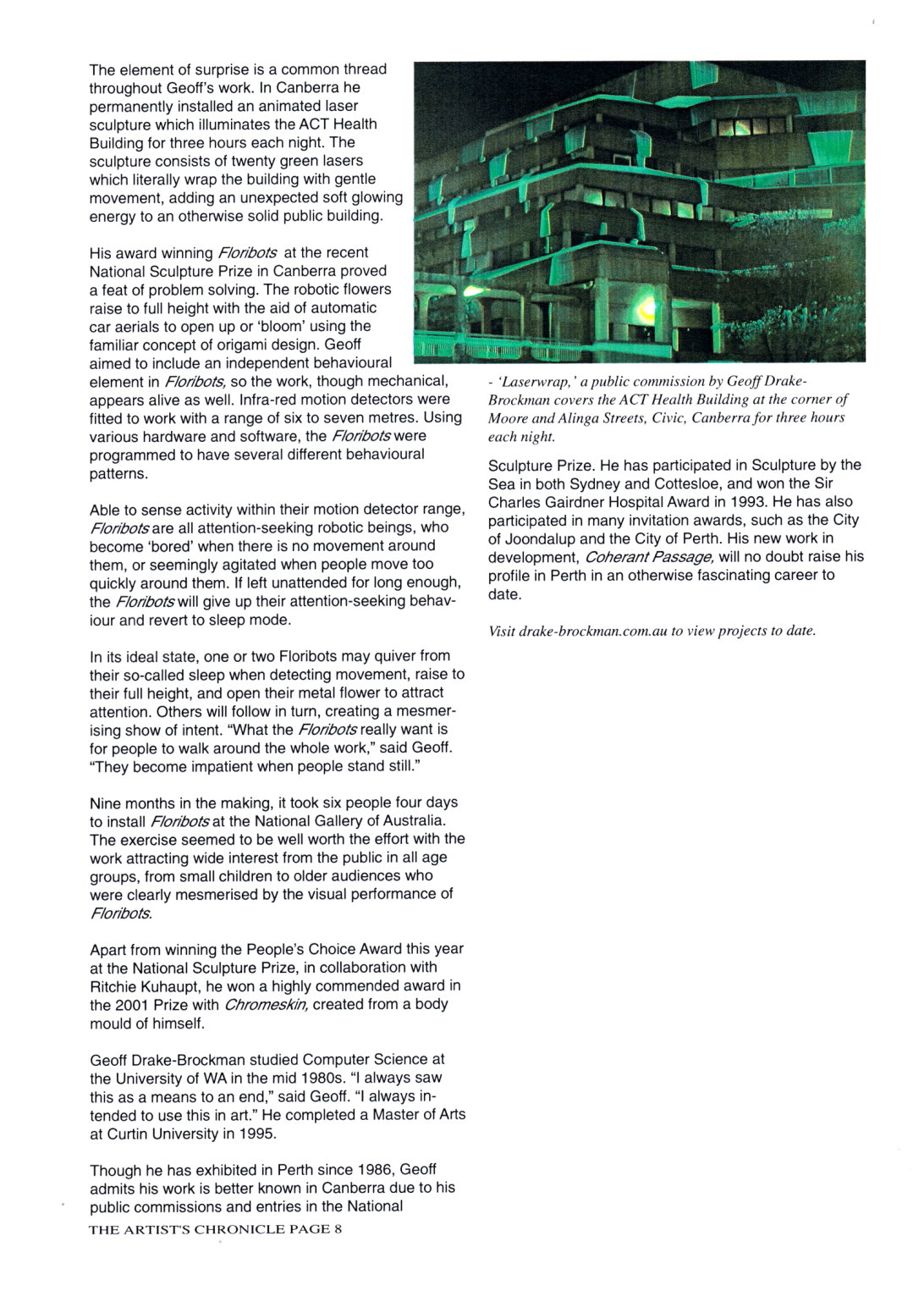

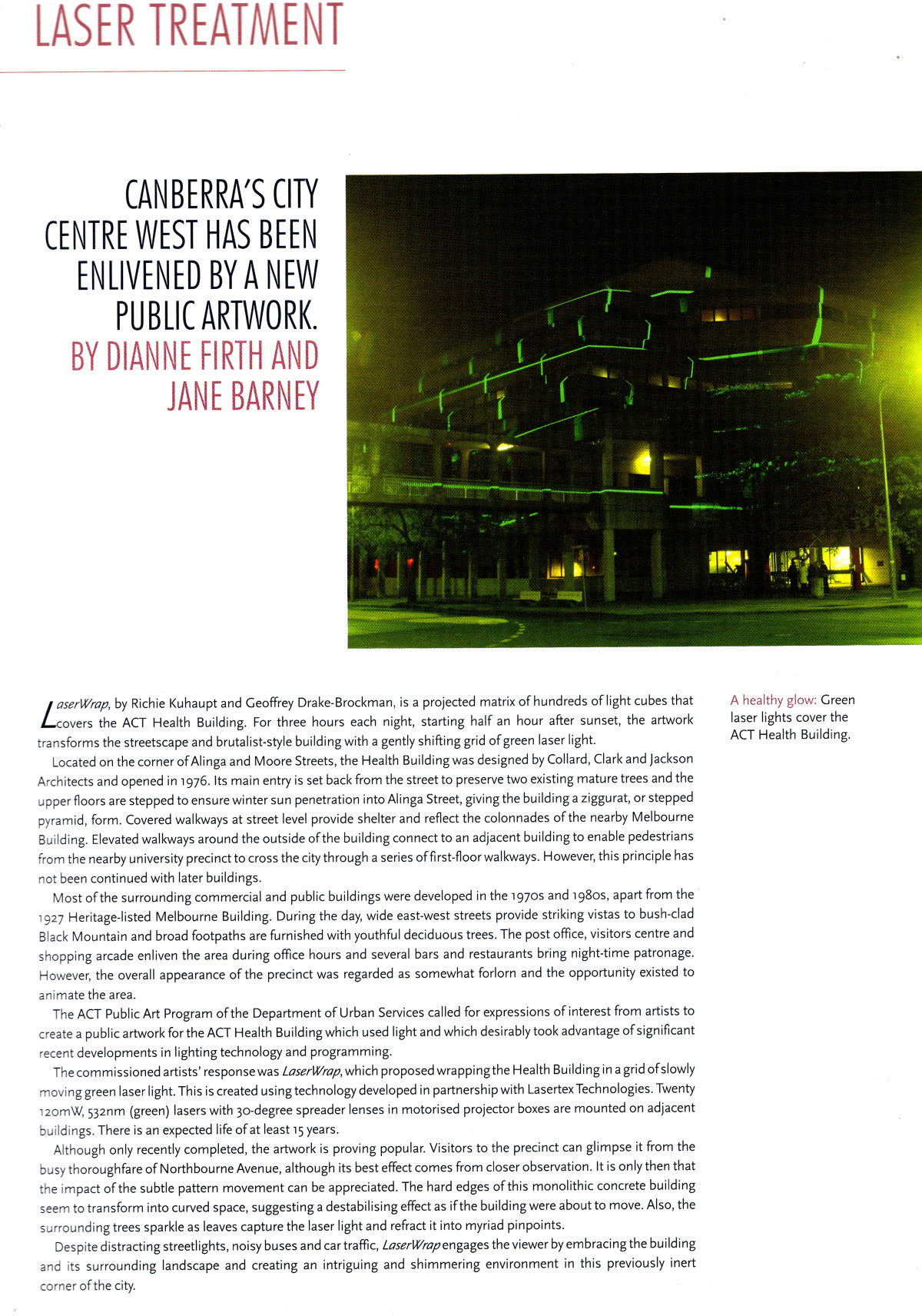

It is through these layers of science fiction and popular culture that Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman’s public art project LaserWrap draws on meaning and effect. The work, while simultaneously demarcating a futuristic, virtual landscape through intense beams of green light does so via a process that operates on recent nostalgia, gleaned especially from viewers of my generation who have an affection for lasers, like they have an affection for pac-man, space invaders and Giorgio Moroder’s “Together in Electric Dreams”. In this work, however, the hopes and desires invested in 1980’s computer technology, and electro-fantasy such as TRON are turned out on themselves. Rather than creating new, impossibly small, virtual spaces for humans to inhabit, this laser technology is projected back outside the system and towards the massive external surfaces and textures of the lived environment.

Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman’s treatment of the ACT Health building is one that could be applied to many sites in this designed city of broad, tree-lined boulevards and parkland interconnecting the behemoths of bureaucracy and institutionalised learning that make up Canberra’s urban morphology. After dark, LaserWrap transforms the ACT Health Building’s mandatory, crème-coloured concrete and brutal, pyramid-like exterior into a glowing object further denuded of depth and it’s daytime ziggurat mass. Each laser projected onto the building is destabilised by a rotating axial mount that arcs the laser line, converting the once solid and undeniably present building into a chimera; a shimmering, illusory object. It appears as if the building’s virtuality is exposed by a glitch in its very own vertical hold as it flickers and strobes throughout the night, only to re-collect its solid mass at dawn.

Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman describe the reductionist visual effect of the lasers as “essentialising”, removing the “surface, colour and texture, to purify, denature and crystallise” objects as a means of attaining pure form. Their work in both LaserWrap and the earlier Lasercube (a smaller, internal version) uses and makes reference to both Cartesian and perspectival systems familiar and indeed essential to pre-modern, Western painting since the Renaissance whereby complex landscapes were divided into manageable parts. By throwing grids of light over external objects, Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman expose the possibility of “essentialising” any landscape or style, from the monolithic and the minimal to the baroque. In this case however, the agitated nature of the LaserWrap alludes to something shifting and fragmenting in the environment, suggesting perhaps that the architectural megaplex has had its day in the sun.

Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman’s collaborative practice is marked by a predilection for ascribing systems; both mathematical and technological onto familiar archetypal forms. As a solo artist Richie Kuhaupt’s sculptural work has evolved through a singular focus on the dissection and extrapolation of the human morphology in work such as the Little Men series. Here Kuhaupt segmented and stratified multiple moulds taken from a single man with obvious allusions to the big medical science breakthrough of the 1990’s, The Visible Human Project which saw an executed prisoner’s body frozen and laser-cut into thousands of photographable cross-sections. Despite the processes of expansion, contraction and distention applied to the body-cast and its layers, each figure retained an undeniable humanity, or an inability to be entirely obliterated of character and individuality. Bad posture, scoliosis, or just plain tired slouching; this humanness, expressed through or in spite of an imposed process, remains a central concern to Kuhaupt’s practice. In collaboration with Drake-Brockman this obsession is carried forward towards a complex dialogue about the nature of art practice in the current technological moment.

As an artist whose solo sculptural practice tends towards imposing, non-figurative objects, Drake-Brockman introduces the viewer as complicit agent in his work by combining surface qualities that both reflect and eschew the real world. These sculptures, reference notions of the digital agent or ‘bot’ exist in the landscape as if extracted accidentally from a virtual frame. They intrude upon environments with loud, highly polished automotive paint and the kind of repetitive patterning made popular by 90’s computer ‘wallpaper’. The work begins to absorb the landscape via chrome nodes, and rippling surfaces, somewhat reminiscent of sci-fi notions of assimilation or replication. As an artist whose work traverses both manual and digital worlds, Drake-Brockman matches Kuhaupt’s applied processes with an awareness of interconnecting technological objectives (he is also a computer systems analyst).

Together their collaborative work begins to question the nature of perception and techno-fascination, specifically in reference to their Chromeskin (2001) installation first shown at the National Sculpture Award at the NGA. This work pitched a highly reflective life-sized chrome figure of a man in direct opposition to its virtual replica. Equipped with four plasma screens, four cameras and sophisticated image-mapping programming, this monolithic technological structure literally mirrored the surrounding gallery environment in exactly the same way as the static figure. What emerged from the observation of public interaction with this work was that layers of mediated and filtered reflection with a virtual object were infinitely more interesting than mere interface with the physical materiality of the original.

The tendency towards narcissism in viewers when confronted with the re-presentation of themselves by an artwork was followed-through by Kuhaupt and Drake-Brockman in their LaserCube (2001) project. The work set up a dual system of transmission and reflection within the cube’s laser grid interior by including a feedback-loop on a TV screen. This enabled the viewer/participant entering the cube to control the representation of their own movement and ultimately to perform for other viewers outside, watching their trace on plasma screens.

With LaserWrap, it is climactic conditions, trees and ephemera rather than human movement that work in tandem with the rotating laser armatures to create the appearance of a shifting, unfixed entity. The beauty of LaserWrap is in its ability to map and elucidate while simultaneously reducing complex structural forms to simple geometries in space. This is a sight that will no doubt be appreciated by students from the national university, and other passers by, gazing through its intangible matrix into the "real world" ordered landscape of Canberra that lies beyond its shimmering green edifice.

Bec Dean, 2004

LANDSCAPE AUSTRALIA - JOURNAL OF THE INSTITUTE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS

Laser Treatment

By DIANNE FIRTH AND JANE BARNEY

Published: Volume 6(3) 2004 - Issue 103

THE NEW YORK TIMES

Using

Illumination

to Truly See

By BENJAMIN GENOCCHIO

Published: 28 December

2003

ART REVIEW; Using Illumination to Truly

See

ALTHOUGH mostly in the dark, ''The

Luminous Image VI'' at Collaborative Concepts here is

all about light. Organized by Franc Palaia, the

exhibition brings together two dozen national and

international artists making photo-based artwork in

which illumination is an integral element. Contributions

range from light boxes and video projections to

illuminated photo sculpture and window transparencies.

''The Luminous Image VI'' is the sixth in a series of exhibitions of art using light organized by Mr. Palaia since 1996. (Bar one, in Italy, all these exhibitions were in galleries and museums in the United States.) This is by far the largest installment in the series, and with so many stylish inclusions I'm guessing it's among the best.

So what have we got? First up, this is the kind of exhibition that encourages thoughtfulness. That means you've got to work a bit, to spend time with the artworks to understand what's going on. If that seems like an imposition, and it is, sort of, then rest assured that most pieces repay patient viewing. Some you'll even want to see again.

Nina Katchadourian's video ''Endurance'' (2002) is thoroughly captivating. It consists of an enlarged close-up of the artist's open mouth, with one of her central teeth serving as a projection screen for film of Sir Ernest Shackleton's doomed (1914-1916) Antarctic expedition - part of the film shows his ship being crushed by ice. The video lasts 10 minutes and the artist keeps her mouth open the entire time.

Ms. Katchadourian's comfortless pose is an act of endurance. She is in pain, as witnessed by her contorted face and the repeated sounds of slurping on the video's minimal soundtrack. Pools of saliva build at the edges of her mouth, eventually spilling over. We are meant to empathize with her stoicism, mirroring that of the explorers.

Equally enthralling is an installation by Richie Kuhaupt and Geoffrey Drake-Brockman. ''Essentialiser'' (2003) consists of a darkened wooden cube crisscrossed with lasers arranged in a grid, meaning that anything in the cube is embedded in a matrix of little cubes of red light. Activity inside the cube is monitored by an infrared camera, and then displayed inside and out as a laser-generated model on feedback monitors. It's all very complicated.

Mr. Kuhaupt's and Mr. Drake-Brockman's futuristic installation is perhaps the freakiest work in the exhibition. I say that not for what it is, but for what it represents. Here, the body is mapped and then reduced to bare geometrical data. It is the electrical equivalent of cloning, with the laser beams transforming people into coded information and then creating virtual replicas. Is that scary? I think so, or maybe I've been watching too many sci-fi films.

Projection and visual reproduction are also central to Debra Pearlman's installations. Of the artist's three works in the exhibition, the best is ''Sleep'' (1990), a sandblasted image in glass set into a tabletop placed above a mound of sand. When light is shined through the glass, the shadow of two children appears on the sand. It is a subtle, clever work.

Peter Sarkisian is perhaps the best-known artist in the exhibition. His ''Book Series #28'' (1997) uses a video monitor concealed in a pile of books beneath a magnifying glass. The video image, visible through the magnifying glass, matches the missing section of the image on the cover of the book, in this case a classical painting of a naked woman. Every now and then, the woman's hand moves between her thigh and mid section. It's creepy.

Various kinds of light boxes (popular these days with artists to display photographs) can be found in the exhibition. Examples include David Michalek's photographs of homeless people, Elizabeth Cohen's and Michael Talley's X-ray photographs, Greg Geffner's 3-D stereoscopic light prints, Kristin Anderson's digital portraits with moving text, Kiki Seror's X-rated cyber sex stories. All are clever, engaging, and well made.

Sensual and lonesome, Shimon Attie's projection photographs kept drawing me back. One of them, ''Untitled Memories'' (1998) shows a prosaic apartment scene into which a reclining male figure has been projected. He is lying on a bed, drinking beer and watching television -- his fuzzy reflection all that can be seen on the television screen. It's an unsettling image, one that gets more and more intriguing the longer you look.

Finally, John Kalymnios deserves mention. At first, his light box images of clouds appear fairly unremarkable. Look closer and you'll see the surface is actually a piece of carved Corian plastic. The Corian has been expertly carved using a fine laser directed by a computer, with each image requiring hours of work. Without doubt, these works are among the most poetically beautiful and technically ingenious in the exhibition. And that is saying something.

''The Luminous Image VI'' is at Collaborative Concepts, 348 Main Street, Beacon, through Feb. 2. Information: (845) 838-1516.

Photos: ''Married by Dusk, Killed by

Dawn (one thousand and one nights)'' by Kiki Seror,

left, is part of an exhibition of artworks using light

at Collaborative Concepts. ''Essentialiser,'' top right,

is a futuristic installation by Geoffrey Drake-Brockman

and Richie Kuhaupt. Below right: ''Untitled Cloudscape

#1 & #3,'' part of a series by John Kalymnios.

Mnemotech : sense + scape + time + memory

By DOROTHY ERICKSON

Published: Vol 22 no 4, 2002

Mnemotech : sense + scape + time +

memory

...

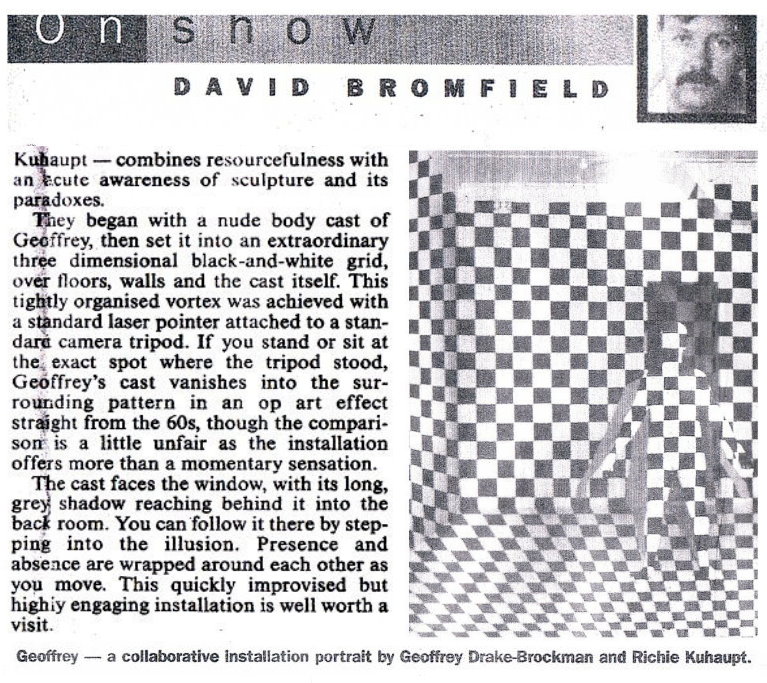

Kuhaupt, who is well known for his cardboard section sculptures, and Drake-Brockman, who has a Master of Arts in addition to his Bachelor of Computer Science degree, started collaborating in 1998, taking out a commendation in the National Sculpture Award in Canberra in 2001. The new work Essentialiser: Lazercube III, explores the potential of laser mapping to create an interactive artwork. A large cube in the centre of an anteroom and four plasma screen panels on the wall are the basic pieces. The interior of the cube is gridded with infrared laser beams. When someone enters the box the laser beams map the body in three dimensions and these mapping lines are projected on the screen outside, moving when the subject moves. Three groups of people entered when I was there creating interesting and at times beautiful effects. Technical limitations also created bizarre images particularly with the first two - a father and son - the father wearing a dark shirt and the son dark trousers. The lasers could not read the dark clothing and so two half-body shapes wove in and out of each other with the horizontal lines always hurrying to catch up to the vertical. The next participant created a dance in her time inside. The graceful movement combined with a slight time lapse had a pair of dancers closely shadowing each other.

CRAFT ARTS INTERNATIONAL

National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition

By BEATRICE GRALTON

Published: No. 54, 2002

NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA

Chromeskin - National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition - Artist's Statement

By GEOFFREY DRAKE-BROCKMAN & RICHIE KUHAUPT

Published: 2001

Chromeskin

Essay from Catalogue of the National Sculpture Exhibition: - The National Gallery of Australia

Our intention from the outset of the Chromeskin project, back in mid-1999, was to make an artwork that consisted of two aspects, physical and virtual, arranged in counterpoise. To do this we would blend traditional sculpture with industrial electrochemical processes, 3-D scanning technologies and multimedia techniques in digital image rendering and animation.

In this project we have made use of chrome in order to harness its rich semiotic impact. Chrome is a null surface - a reflection that only quotes the world that it inhabits. Chrome is a cyberpunk reference symbol that signifies a technology-saturated world where street culture is imbued with virtual and body-invasive supertechnologies. Chrome is the sanitised, smudge-free surface of the perfect housekeeper's pristine kitchen appliances. Chrome is an automotive effect from the heyday of American industrial dominance in the 1950s and 1960s when the automobile was celebrated as mechanical fetish and sexual extension. Chrome is a pop culture referent for supertechnology - the surface of the robot in Terminator II - the ultimate 'liquid metal' machine.

The departure point for Chromeskin was a human bodycast. We knew we wanted a male figure - an office worker physique, about 1.8 metres tall and carrying a bit of weight. Drake-Brockman provided an appropriate physical form, while we were able to draw on Kuhaupt's extensive experience with body-moulding during the casting process. We prepared a series of positive and negative moulds; some elaboration of the cast re-established features lost along the way. We ended up with a hollow fibreglass casting that we used as a 'master' for subsequent stages of the project. This master cast became the basis of two initially divergent paths.

One path entailed the preparation of a full size physical Chromeskin - a chromium-plated, mirror-finished mannequin - via electroforming and electroplating technology. First, a layer of copper was electroformed over the fibreglass body elements in a plating bath. After polishing, layers of nickel and chromium were deposited to complete the surface. The process of chrome plating over a non-conductor was similar to that employed by Drake-Brockman in previous artworks.

The second path, which progressed in parallel with the first, was the creation of a virtual Chromeskin 'inside the machine'. To achieve this, the master cast was surface-digitised using a laser 3-D scanner. Then, via 3-D modelling software, the scan outputs were rendered to seem like chrome and the created body was animated within virtual space.